When Tulsa Mayor G.T. Bynum stated in his 2018 State of the City address that opportunity needed to be accessible for all Tulsans, he echoed a concern held today by most mayors in the United States. Bloomberg’s 2018 American Mayors Survey identified economic opportunity as one of the biggest priorities for mayors. As these mayors attempt to close the opportunity gap in innovative ways, it’s important to consider where and for whom opportunity is lacking.

When Tulsa Mayor G.T. Bynum stated in his 2018 State of the City address that opportunity needed to be accessible for all Tulsans, he echoed a concern held today by most mayors in the United States. Bloomberg’s 2018 American Mayors Survey identified economic opportunity as one of the biggest priorities for mayors. As these mayors attempt to close the opportunity gap in innovative ways, it’s important to consider where and for whom opportunity is lacking.

Opportunity Gaps are Greatest for Black Men

In 2018, we released Race and Economic Opportunity in the United States: An Intergenerational Perspective, which highlighted race as one of the key factors that affect a child’s upward mobility. The American Dream is increasingly out of reach for all persons in the United States, but our research suggests that the opportunity gap is greatest for Black men. Not only are Black men less likely to move up the income ladder, but, even when they grow up in high-income families, they are more likely to lose economic ground compared to their parents.

Tulsa, a member of the What Works Cities Economic Mobility Initiative, offers an example of how mayors can use this finding by targeting their efforts and programming to spur opportunity growth for Black men in their communities. With the Opportunity Atlas at their disposal, mayors and their offices have been better equipped to analyze—down to the neighborhood level—the parts of their cities that are most affected by these disparities.

Applying Opportunity Atlas Findings in Tulsa

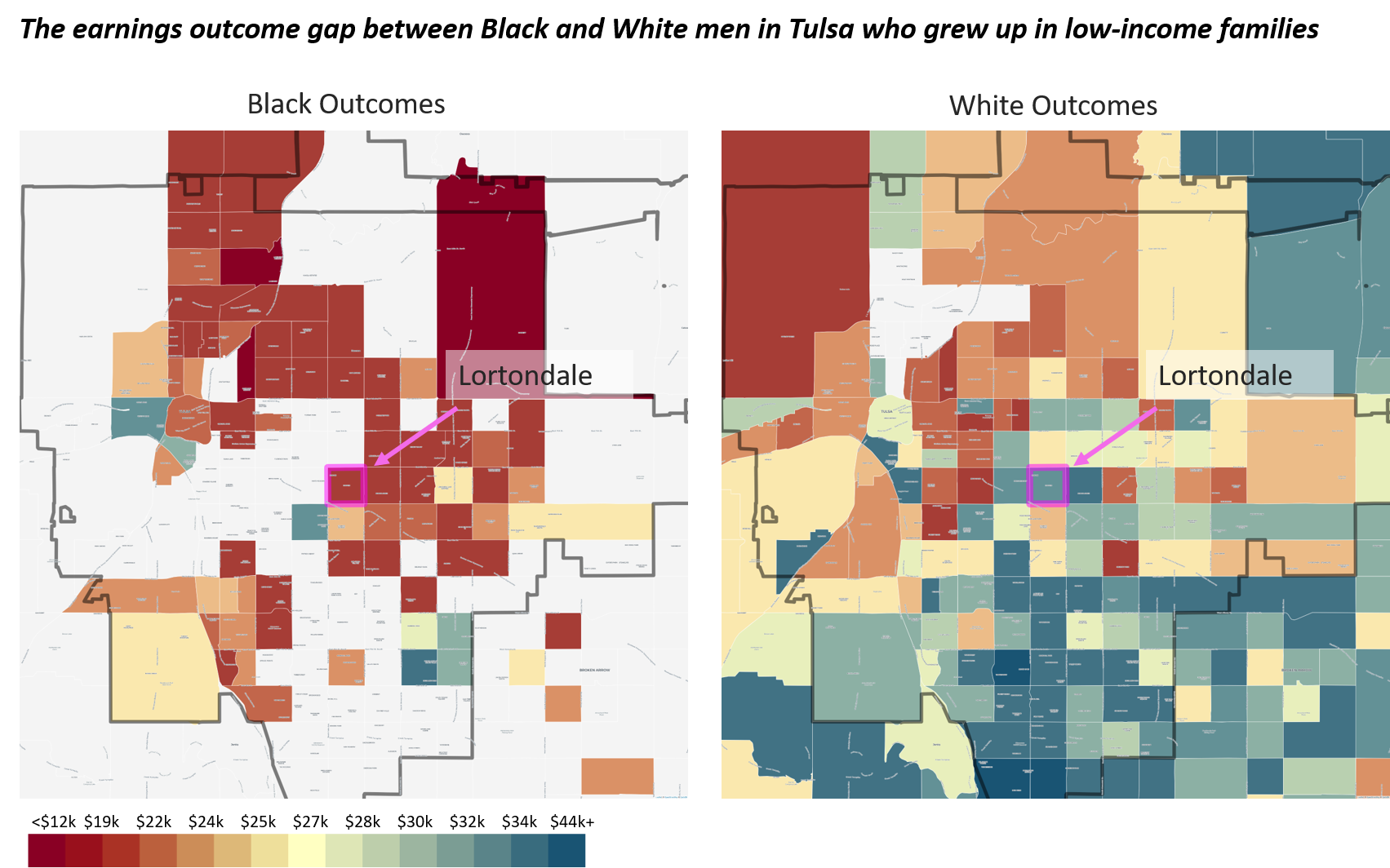

The Opportunity Atlas reveals that in Tulsa, outcomes for Black men growing up in low-income families vary significantly by neighborhood.

Moreover, a closer look reveals striking opportunity gaps between Black and White men specifically. In Lortondale, a neighborhood located in South Tulsa, Black men who grew up in low-income families had average earnings less than half that of White men from low-income families from the same neighborhood ($13,000 vs $34,000, respectively).

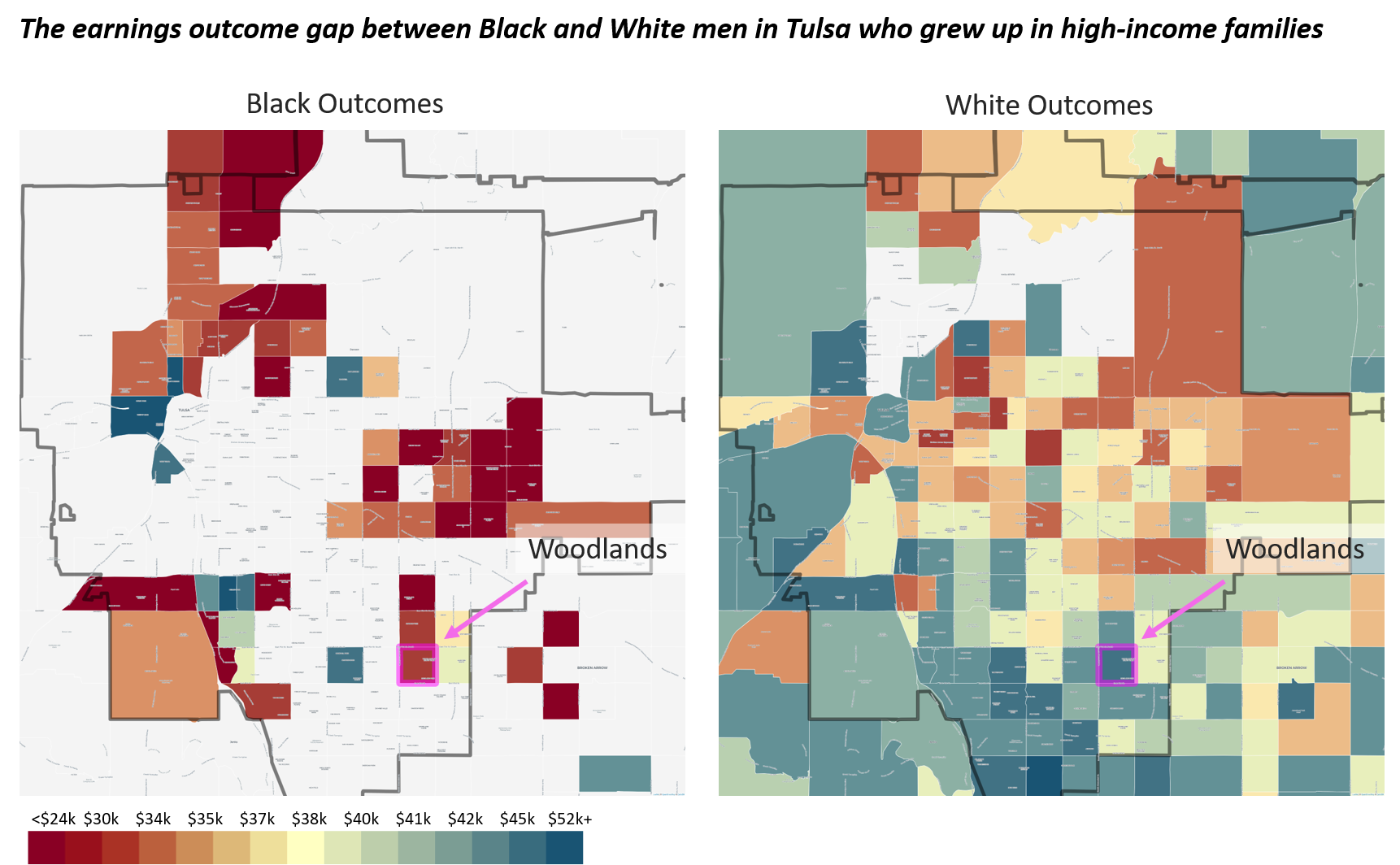

These race gaps extend beyond parental income level. For example, Black and White boys who grew up in high-income households in the Woodlands neighborhood had a nearly $20,000 income gap in terms of average earnings by adulthood.

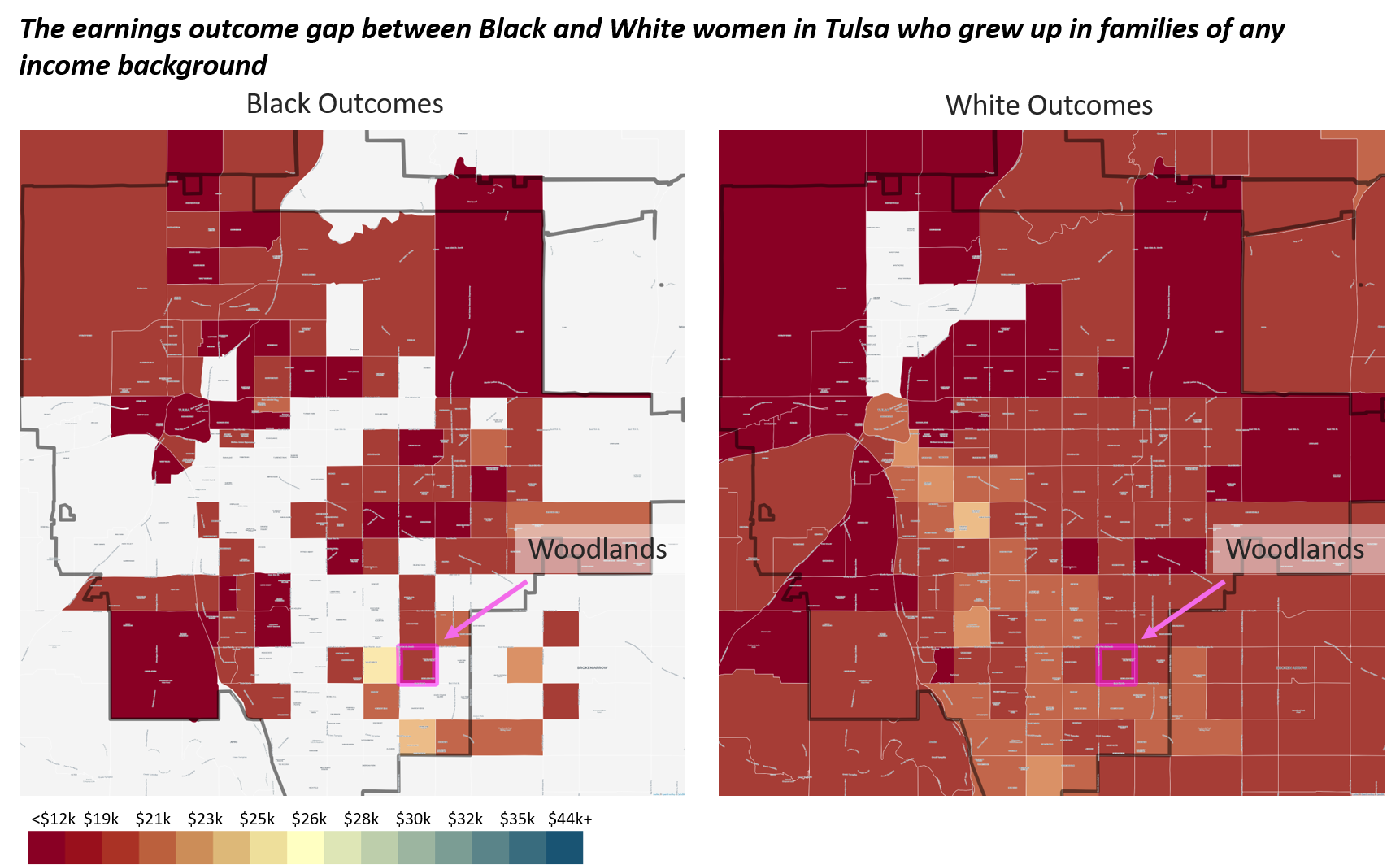

It is important to note that racial opportunity gaps are largely due to differences in men’s and not women’s outcomes. In the Woodlands neighborhood, for instance, Black women from every parental income level had much closer outcomes (average earnings of $24,000) to White women with comparable parental income levels (average earnings of $28,000).

For mayors focused on addressing economic mobility gaps, results such as these from the Opportunity Atlas suggest a need for policy solutions that intentionally work to increase upward mobility for Black men.

Tulsa’s Greenwood District

In order to apply findings from the Opportunity Atlas, it is also critical to consider history and community context to effectively tailor efforts to address opportunity gaps.

In the early twentieth century, Tulsa’s Greenwood District was home to more than 300 Black-owned businesses, earning it recognition as “Black Wall Street” and one of the most successful Black neighborhoods in America. After the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre destroyed much of the community’s establishments, Greenwood worked diligently to rebuild itself. When Tulsa decided in the 1960s and 1970s to introduce urban development initiatives—including a highway that ran through the heart of the district—it cut-off a significant portion from what is left today.

Today, Greenwood remains a majority Black community. Average earnings for low-income Black men who grew up in the area is around $24,000, a figure that lags the average earnings of low-income Black men from other neighborhoods.

Keeping Context at the Forefront of Policy

A historically- and data-conscious initiative is taking shape in Tulsa, where the city is overseeing a master redevelopment plan of the Kirkpatrick Heights-Greenwood area within the boundaries of the Historic Greenwood District. This ongoing process seeks to be community-informed and aims to bring back commerce and residents to this neighborhood of historical significance.

To this end, the city is working to support low-income residents through its Affordable Housing Strategy’s focus on homeownership as well as through employment programs under consideration as part of the 36th Street North Economic Development Plan. Additionally, Tulsa is prioritizing the recruitment of young Black men and NextUp participants for its newly developed Maxwell Fellowship.

Moving Forward

“I ran for mayor because I believe all Tulsans, no matter where they live, should have an equal chance at a great life in our city,” says Mayor G.T. Bynum. “Life expectancy shouldn’t be determined by where you live in Tulsa and that is why we have started working to address opportunity gaps that will help build the foundation for economic prosperity, improve health and enhance quality of life. Our work starts with economic development policies and programs to drive employment to underserved areas while providing training opportunities for those that need it most. Affordable housing and social connectivity are other areas where we are taking necessary steps to decrease the life expectancy gap.”

In Tulsa, the Opportunity Atlas has provided new insights into opportunity gaps in the city and has highlighted the need to target efforts for increasing opportunity for Black men. Similar applications of neighborhood-specific results from the Opportunity Atlas may prove useful to mayors across the country focused on closing opportunity gaps in their own communities.

*As the Opportunity Atlas captures outcomes at the Census tract level, this does not always conform to historical or current neighborhood boundaries. As such, the analysis above focuses on the most representative Census tract that encompasses most of the area of the Historic Greenwood District.