The Opportunity Atlas allows users to see the geography of upward mobility in their communities by showing the effect of different places on children’s adult outcomes. By observing how opportunity varies at the neighborhood level, policy-makers, practitioners, and others can better understand where and how long term outcomes can be improved locally.

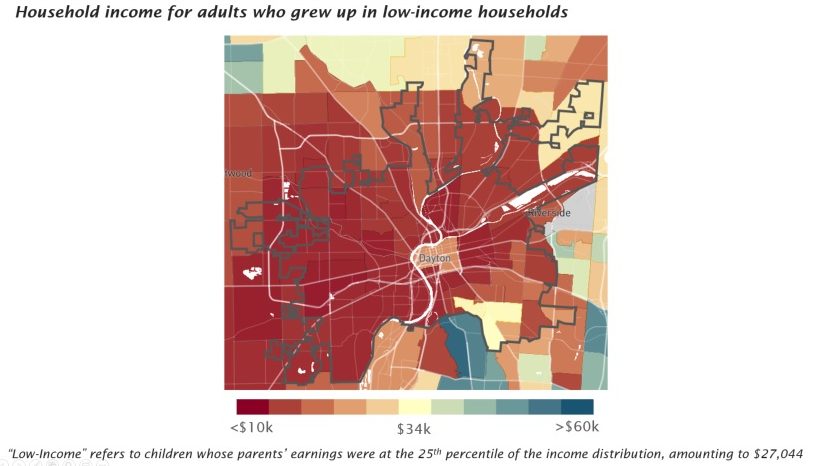

One frequent pattern across cities in the Atlas is a high degree of variation at local neighborhood levels. In a hypothetical town, the average low-income child might grow up to have an income of $35,000 [1], but at the neighborhood level, it is common for this figure to range upwards of $15,000 above and below the city’s average.

Such instances of intra-city variation imply a two-pronged policy pathway for improving mobility. In the shorter term, cities can support policies to increase children’s access to higher-opportunity neighborhoods that already exist. And in the longer term, cities should target efforts to reinvest and create more opportunities in the neighborhoods that need support.

The Geography of Upward Mobility in Dayton

Dayton, Ohio – like other cities in America’s Rust Belt – shows a different mobility landscape. While a low-income child who grows up in the average Dayton Census tract can expect a household income of around $23,000 at age 35, most tracts in the city do not significantly differ from this average. Such city-wide consistency is striking and suggests the need for city-wide policy solutions that can support every neighborhood.

The Dayton region has an entrenched history of segregation, and poverty is overwhelmingly concentrated within its boundaries. These factors have contributed to most higher-opportunity neighborhoods being located beyond the urban center.

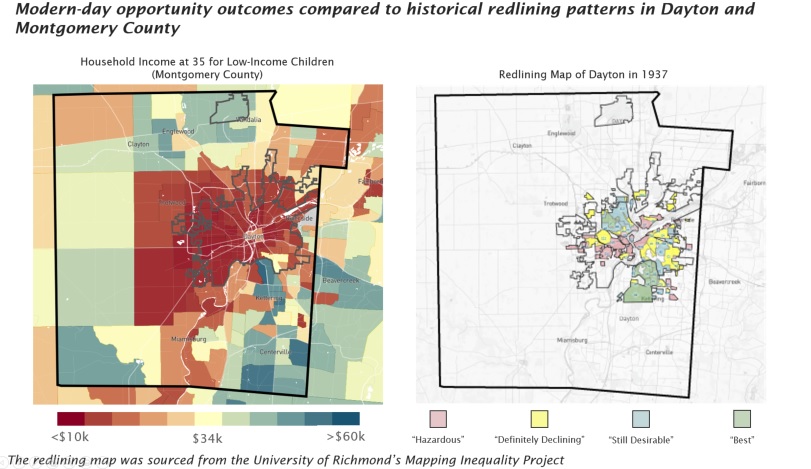

From the mid to late 20th Century, Dayton was buffeted by redlining, deindustrialization, highway construction that destroyed stable neighborhoods, and flight to the suburbs, leaving the city with many more poor residents than its suburban neighbors. These forces contributed to today’s opportunity pattern by fueling population decline, depressing property values, and reducing investments in the city[2].

“Our wider community has a legacy of segregation and systemic racism that continues to disadvantage Dayton, making it infinitely harder to foster mixed-income neighborhoods, strong schools and ensure equitable opportunities and upward mobility,” said Torey Hollingsworth, Senior Policy Aide to Dayton Mayor Nan Whaley.

A Case for City-Wide Interventions

The mobility patterns in Dayton suggest that, given city-wide needs, a more fitting strategy may be to identify a broader set of interventions for all neighborhoods. One example is the Dayton-Montgomery County Preschool Promise – an initiative designed to guarantee all four-year-olds access to one year of high-quality preschool. With significant investments by both the City of Dayton and Montgomery County, Preschool Promise is showing success in driving up the quality of instruction at preschools and incentivizing families to choose strong programs. (Tuition assistance increases with provider quality and family need.) A family making below 200% of the Federal Poverty Level ($52,400 for a family of 4) typically gets free Preschool. Preschool Promise is available throughout the City of Dayton as well as in five high-need areas outside the City.

City-wide interventions come with a different set of considerations than those which target specific communities. One of these is how experiences of the intervention may differ across demographic groups. Preschool Promise is intensively working to bridge the all-too-pervasive achievement gap between Black and white preschoolers[3]. Specifically, Preschool Promise is incorporating culturally relevant teaching and anti-bias principles into early childhood educators’ professional development. In addition, it is in the early stages of forming a workgroup of largely Black men to discuss how preschool could better support boys who are Black. Even within their city-wide approach, Preschool Promise is working to meet the needs of different communities.

Though the Opportunity Atlas shows consistent need across Dayton’s neighborhoods, city-wide interventions must consider differences at the neighborhood level that affect program preferences or take-up. For example, place-based data on benefit take-up showed that while a majority of West Dayton families sent their four-year-olds to preschool in the 2017-18 school year, fewer than half of East Dayton families did the same[4]. More work is needed to understand why these neighborhood-level differences exist; in the meantime, Preschool Promise and a local child care provider are developing a mobile preschool pilot that will bring services directly to children in neighborhoods where take-up rates have been lower.

Dayton is also looking to boost Preschool Promise’s impact through participation in the What Works Cities Economic Mobility initiative, which aims to help the nine participating cities identify, pilot, and measure the success of local strategies designed to accelerate economic mobility for their residents[5].

“Preschool Promise is committed to disaggregating data to identify where we have to close opportunity gaps and to serving families the way they want to be served,” said Robyn Lightcap, executive director of the Dayton-Montgomery County Preschool Promise. “Opportunity mapping helps us strategically target resources where they’re needed most.”

Expanding early childhood education is just one part of the broader effort needed to improve upward mobility across Dayton. OI Research shows that higher-opportunity areas also tend to have more social capital, high-quality K-12 schools, and lower poverty rates. But Preschool Promise is an example of how opportunity mapping can inform blanket policies as well as targeted interventions. The Atlas highlights a need for city-wide intervention in Dayton, and Preschool Promise shows the need to consider the differential experiences and take-up of demographic and neighborhood groups.

[1] This represents one’s household income at age 35

[2] Learn more about the history of demographics, economics, and racism in Dayton in the three-part Roots of Racism series, hosted by Dayton mayor Nan Whaley, University of Dayton professors Kelly Bohrer and Leslie Picca, and Will Smith of the Dayton Board of Education

[3] Page 6 of Preschool Promise’s 2017-18 report details the local achievement gap

[4] Page 9 of Preschool Promise’s 2017-18 report shows the distribution of take-up across the city

[5] To learn more about Dayton’s work, read “Dayton Doubles Down on Preschool Attendance.”