Last month, former President Barack Obama was celebrating Black History Month and the five-year anniversary of the launch of My Brother’s Keeper, his Obama Foundation initiative to engage communities across the country in supporting young people to reach their dreams, regardless of their race, gender, or socioeconomic status. The president’s focus is one that is of utmost importance in our country.

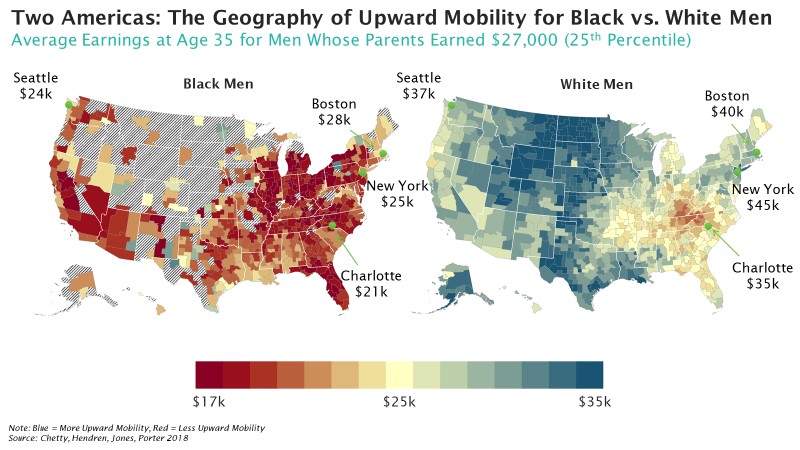

In March 2018, Opportunity Insights released Race and Economic Opportunity in the United States: An Intergenerational Perspective that, among other findings, highlighted how black men across the country have substantially lower rates of upward mobility and higher rates of downward mobility than white men. The black-white gap persists even between boys who grow up on the same block.

Put simply, we are living in two different Americas. In every neighborhood of the US, rates of upward mobility for black men are lower than those of white men.

Nonetheless, there are significant differences in upward mobility for black men across neighborhoods. Overall, our data suggest that the neighborhoods that produce the highest rates of upward mobility tend to have lower poverty rates, more stable family structures, greater social capital, and better-quality schools. In low-poverty neighborhoods, the two strongest factors that characterize places with high upward mobility for black men are low levels of racial bias among whites and high rates of father presence in the community. This factor is important even if the child does not have a father present in their own home; what matters is the share of other households with fathers present.

While our data can tell us a lot about the geography of opportunity in America and how that differs by race, there is a lot that our data cannot tell us about the lived experiences of black Americans. About the access to opportunities we do or do not have. About the role of different forces and systems in smoothing the pathway to opportunity or putting up barriers to it. About what factors I should make sure are in place for my nephew, a black boy growing up in the South, to be successful in adulthood.

To that end, our team is digging deeper into these data to look for best practices and lessons learned from communities across the country that are working to improve outcomes for black Americans broadly and for black men specifically.

Our research shows that race gaps in adulthood are shaped by childhood environments: the gaps in adulthood decline for white and black children who grow up in neighborhoods with more equal rates of upward mobility for black and white children. And, our research shows that every year matters in determining a child’s trajectory.

As a result, we cannot hope for a single “magic bullet” intervention. Rather, we need a broad approach that sustains supports for these children across different points of life, changing as children age and as the appropriate form of support evolves. For instance, high-quality early childhood programs for young children and mentoring supports for older children that help them expand their horizons and connect them with opportunities they may not have had access to otherwise. We must also address policies and practices that limit opportunity for black children.

My Brother’s Keeper’s focus on engaging local communities is the right approach. More information from the ground and innovative ideas are needed to ensure that all children, regardless of race, are on a level playing field. So, what answers are you finding in your communities and in your work? What factors have you seen lead to improved outcomes for the black boys and girls growing up in your city? Do you know of promising policies, programs, or interventions that are making a difference? We are interested to hear what you have found to be most impactful and most harmful in your own communities.

Our data show that if we want to improve upward mobility broadly in America, we must have a concerted focus around improving black opportunity generally and for black men specifically. We can’t do this alone. If you are interested in opening a dialogue with us about this important work, we want to hear from you.

Please reach out to us at [email protected].