Charlotte Opportunity Initiative

Supporting Local Community:

Charlotte Opportunity Initiative Collaboration with community leaders to identify and support data-driven systems change.

We all want the same thing for our children – a shot at the American Dream. It is the idea that no matter where you start in life, you have a chance of climbing up the income ladder and becoming successful.

One of the surprising findings from our work was that Charlotte had the lowest rate of upward mobility of the largest 50 metropolitan areas in the country. We were inspired by Charlotte’s response to those findings. Instead of being discouraged by or seeking to challenge the data, local leaders and community members used 50 out of 50 as a call to action, an impetus for convening difficult conversations and beginning the hard work necessary to build a community where opportunity exists for everyone.

Charlotte’s response reinforced our belief that data and research have the power to create real change. We have been pleased to partner with Foundation For The Carolinas, Leading on Opportunity, and a range of local organizations and individuals on the Charlotte Opportunity Initiative to identify policy areas with the potential to increase upward mobility in Charlotte.

Through this work, we began digging deeper into the data in Charlotte itself to understand why Charlotte ranks low in terms of economic mobility for its kids despite having a vibrant, rapidly growing economy. One encouraging finding in the data is that the roots of economic opportunity lie at a very local level: there are neighborhoods within Charlotte itself where kids from low-income families have good chances of rising up. Although examples of promising programs and policies from across the country can be helpful, identifying success stories within Charlotte provides a more concrete path to replicating those successes more widely across the city.

Our research and collaborative work point to real solutions that can change children’s lives for the better – from affordable housing in higher opportunity neighborhoods to better pathways from school to colleges that successfully propel students up the income ladder.

Our Partners in Charlotte

Key Findings

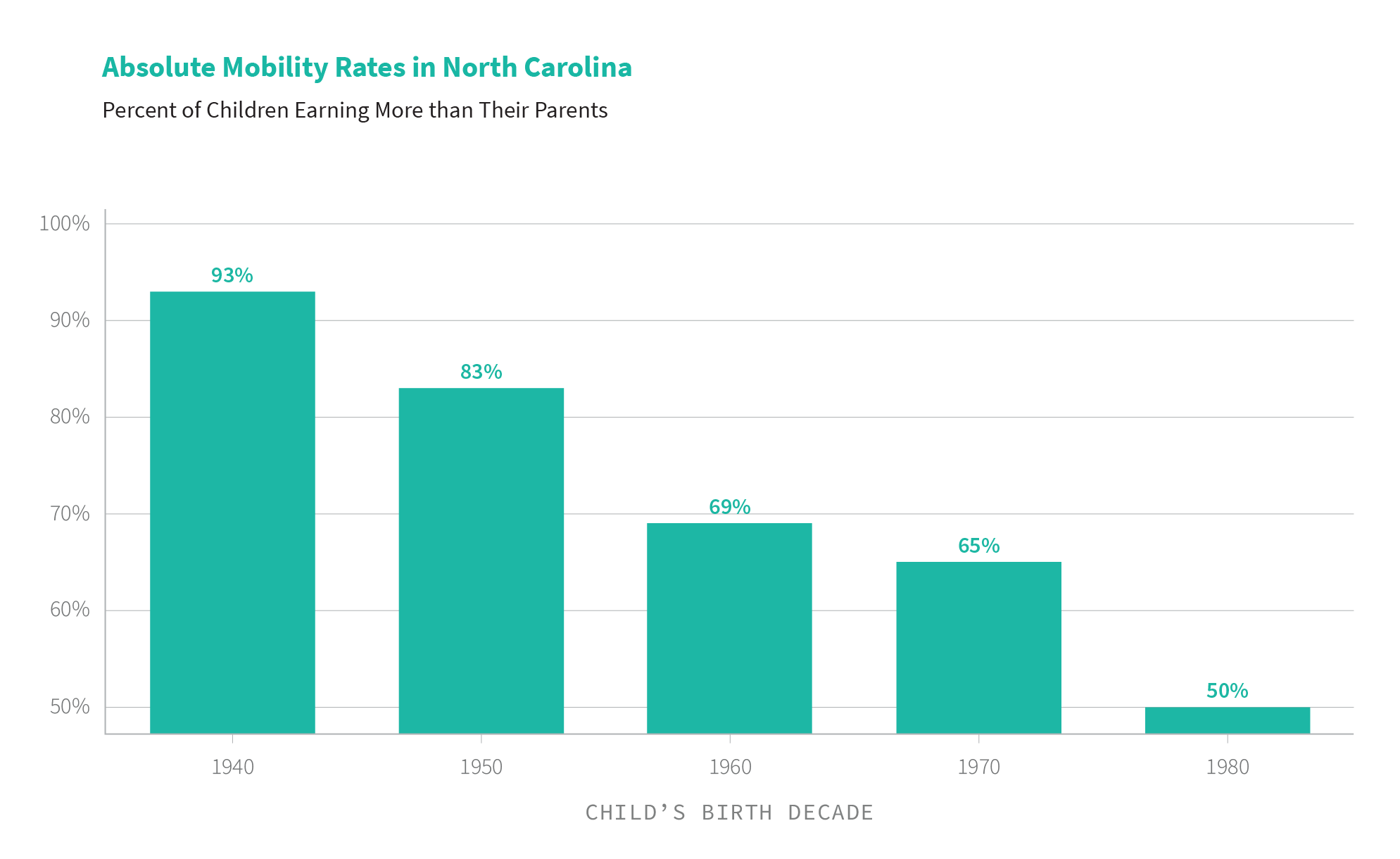

Since the 1940s, the chance that children from North Carolina will grow up to achieve a higher standard of living than their parents has fallen from 90 percent to 50 percent. This is consistent with a pattern we see across the country. Most of this decline stems from increasing inequality. Since 1980, income growth has been much faster at the top of the income distribution than for the poor and middle class. If income inequality were as low as it was in 1940, 80 percent of children would earn more than their parents.

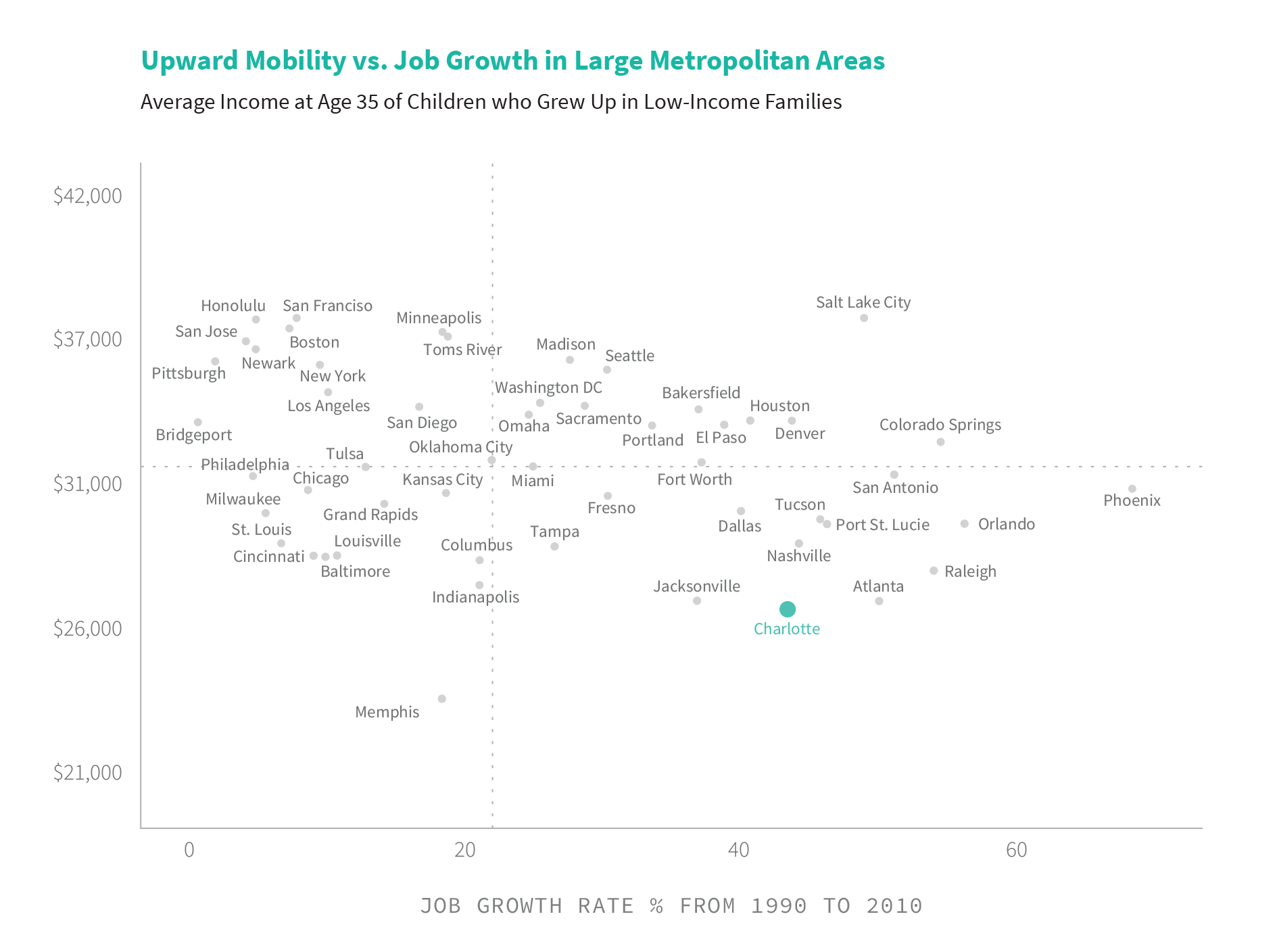

As highlighted in the 2014 “Land of Opportunity” study, low-income children raised in Charlotte only have a 4.4 percent chance of growing up to become wealthy adults, the lowest rate of the largest 50 metropolitan areas in the country. These rates are similar to Southeastern regional neighbors like Atlanta, Raleigh, and Jacksonville. Despite high rates of job growth over the past 30 years in these cities, children from low-income families from these communities have been unlikely to benefit from local economic prosperity. Many of the new, high-paying jobs that have been created in places like Uptown Charlotte are being filled by adults who grew up elsewhere.

Children from upwardly mobile regions like New York City, Boston, Seattle, and San Jose have much greater chances of becoming high-income adults, more than twice that of children in Charlotte. Communities like these with higher rates of upward mobility generally have less residential segregation, less income inequality, better primary schools, higher levels of social capital, and greater family stability.

What do these mobility rates mean for individuals growing up in Charlotte? Children raised in low-income families — families that had household incomes around $27,000 — grow up to earn just $26,000 on average. This is much lower than their counterparts in Charlotte from higher-income families. Children from low-income families are also much more likely to be incarcerated or become teen mothers and are much less likely to graduate from college.

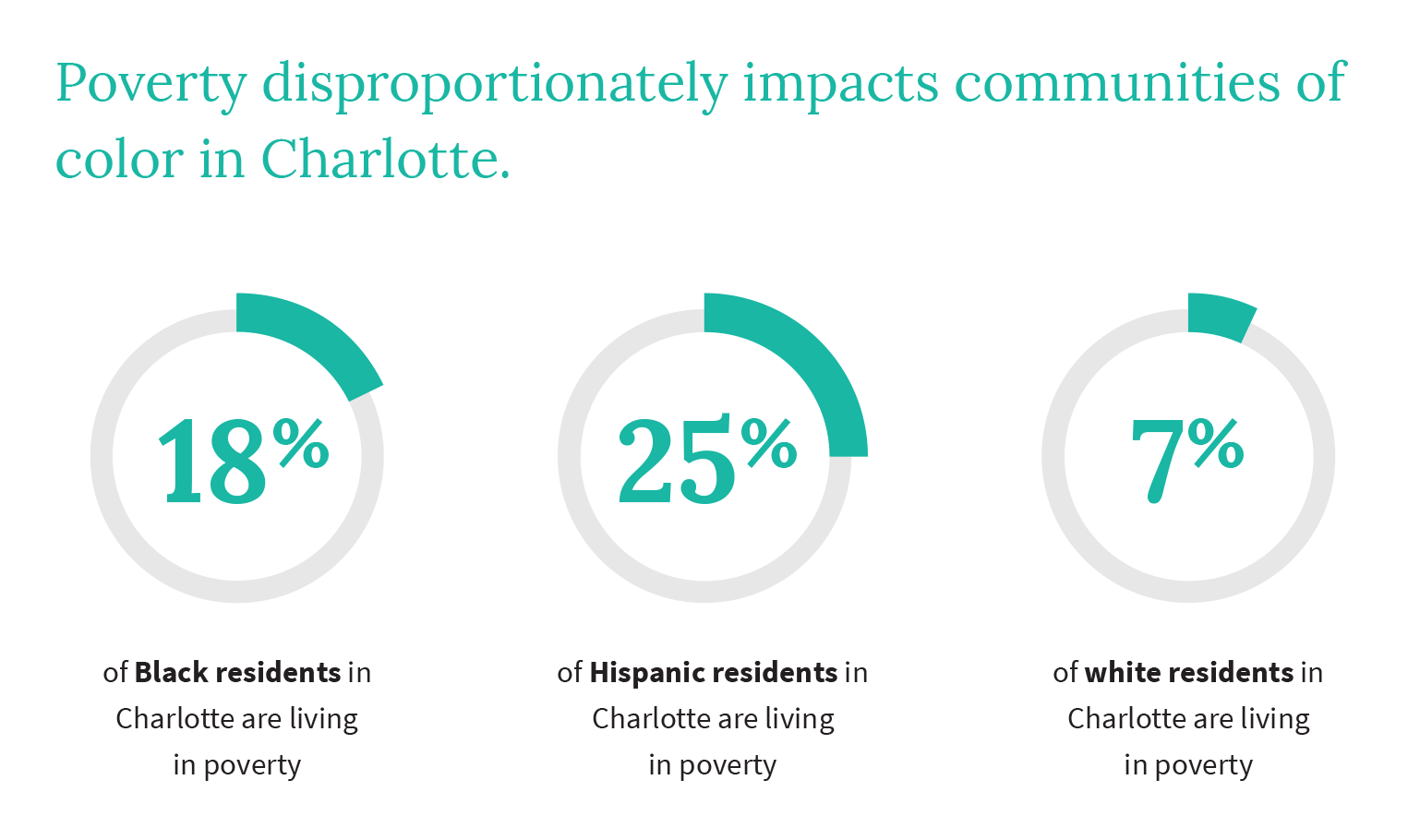

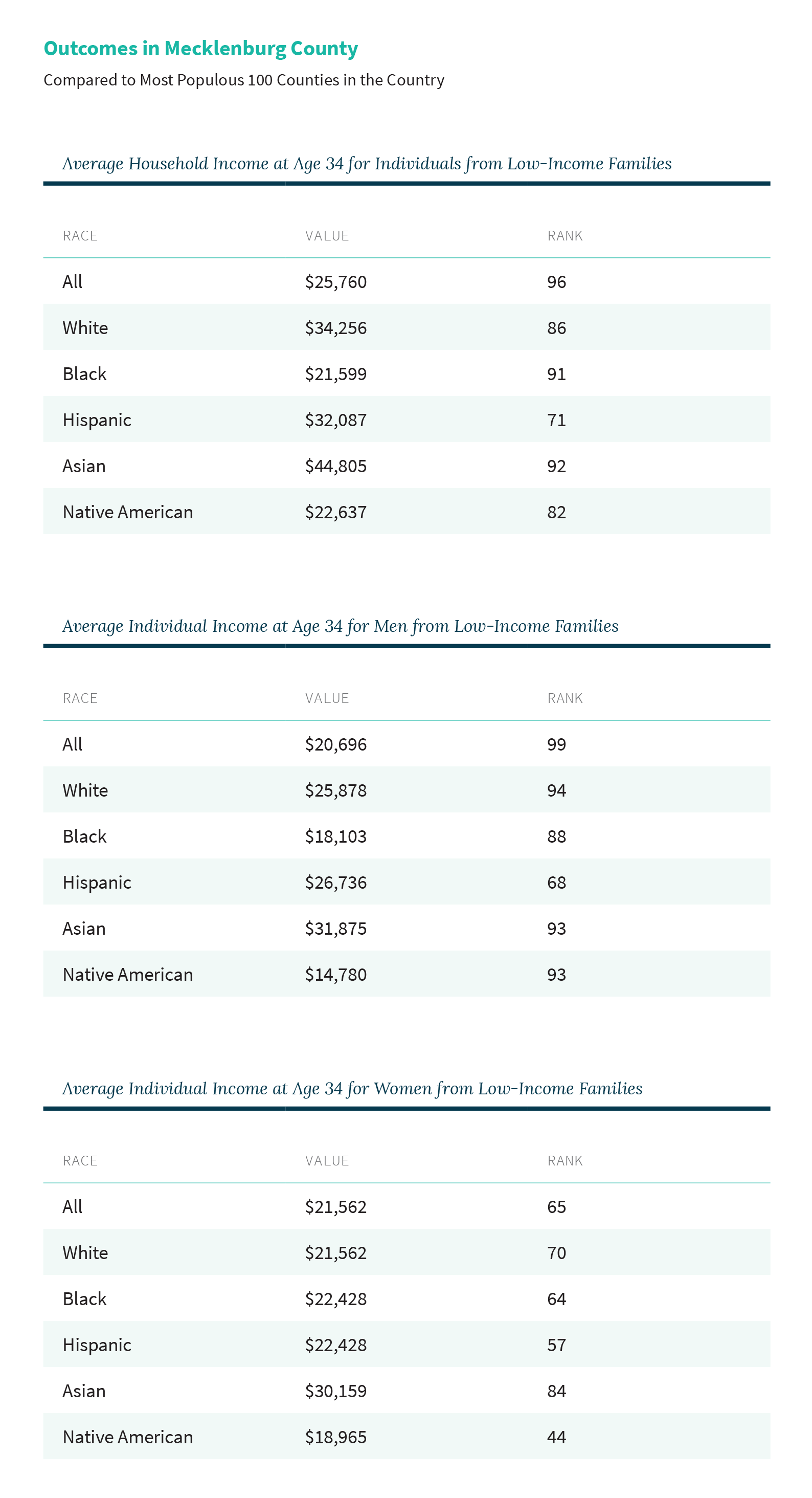

Poverty disproportionately impacts communities of color in Charlotte. 18 percent of Black residents and 25 percent of Hispanic residents are living in poverty, while that number is only 7 percent for white residents. However, low rates of upward mobility across generations impact almost all categories of Charlotteans. For example, white men in Charlotte have very low relative rates of upward mobility. Outcomes for white men from low-income families in Mecklenburg County are lower than outcomes for white men in 94 of the largest 100 counties in the country.

But despite generally low rates of upward mobility for many groups in Charlotte, deep disparities across racial groups also exist within the community. This is especially true between Black and white men. Black men who grow up in low-income families in Charlotte have household incomes of $19,000 on average in adulthood, whereas that number is $32,000 for white men growing up in similarly low-income families.

Although overall economic mobility rates in the region are low, outcomes vary greatly within the region and can differ significantly by neighborhood.

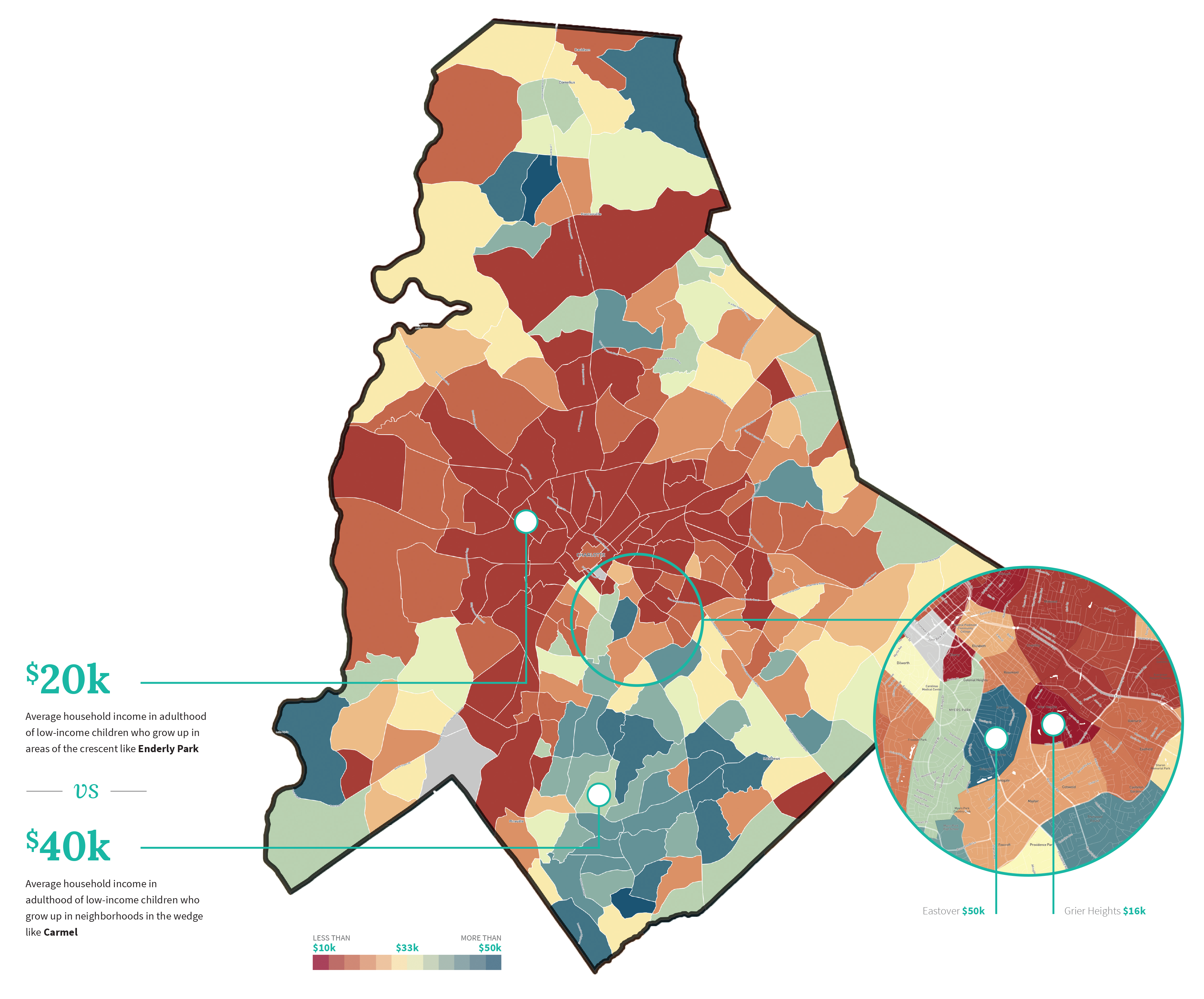

Charlotte’s history of racial and economic segregation drives disparate outcomes between the affluent “wedge” of southern Charlotte and the less wealthy “crescent” in the north, east, and west. Low-income children who grow up in neighborhoods in the wedge-like Carmel grow up to have household incomes of almost $40,000 on average whereas low-income children who grow up in areas of the crescent-like Enderly Park earn less than $20,000.

Outcomes can also differ dramatically across neighborhoods just a few miles apart. For example, stark lines of racial and economic segregation separate neighborhoods like Grier Heights with the neighboring communities of Eastover and Myers Park. Grier Heights is a largely Black neighborhood and has very high poverty rates, whereas its neighbors to the immediate west are over 90 percent white with median incomes of $200,000 in certain areas. These demographic divides are reflected in the outcomes of the children who grow up there. Low-income children raised in Grier Heights historically only grow up to make $16,000 on average in adulthood. Low-income children growing up across the street in some parts of Eastover would be expected to make upwards of $50,000. On the day the Census was taken in 2010, 12 percent of the men that grew up in Grier Heights were incarcerated whereas almost no men from Eastover or Myers Park were in jail or prison.

On the west side of Charlotte, the neighborhood that was once home to Boulevard Homes also had some of the lowest rates of upward mobility in the region. Black men growing up in low-income families earn $15,000 on average in adulthood whereas young Black men in similarly low-income families growing up a couple of miles south in the Old Whitehall neighborhood earned almost twice as much. Compared to Boulevard Homes, Whitehall had a much higher proportion of black fathers present in the community, a factor that we see associated with higher rates of upward mobility for young black men specifically in Charlotte and throughout the country.

The same neighborhood can also impact different kinds of children in different ways. In Country Club Heights in east Charlotte, white men in low-income families grow up to earn $34,000, while their Hispanic and Black counterparts growing up in the same only area earn $29,000 and $20,000 respectively.

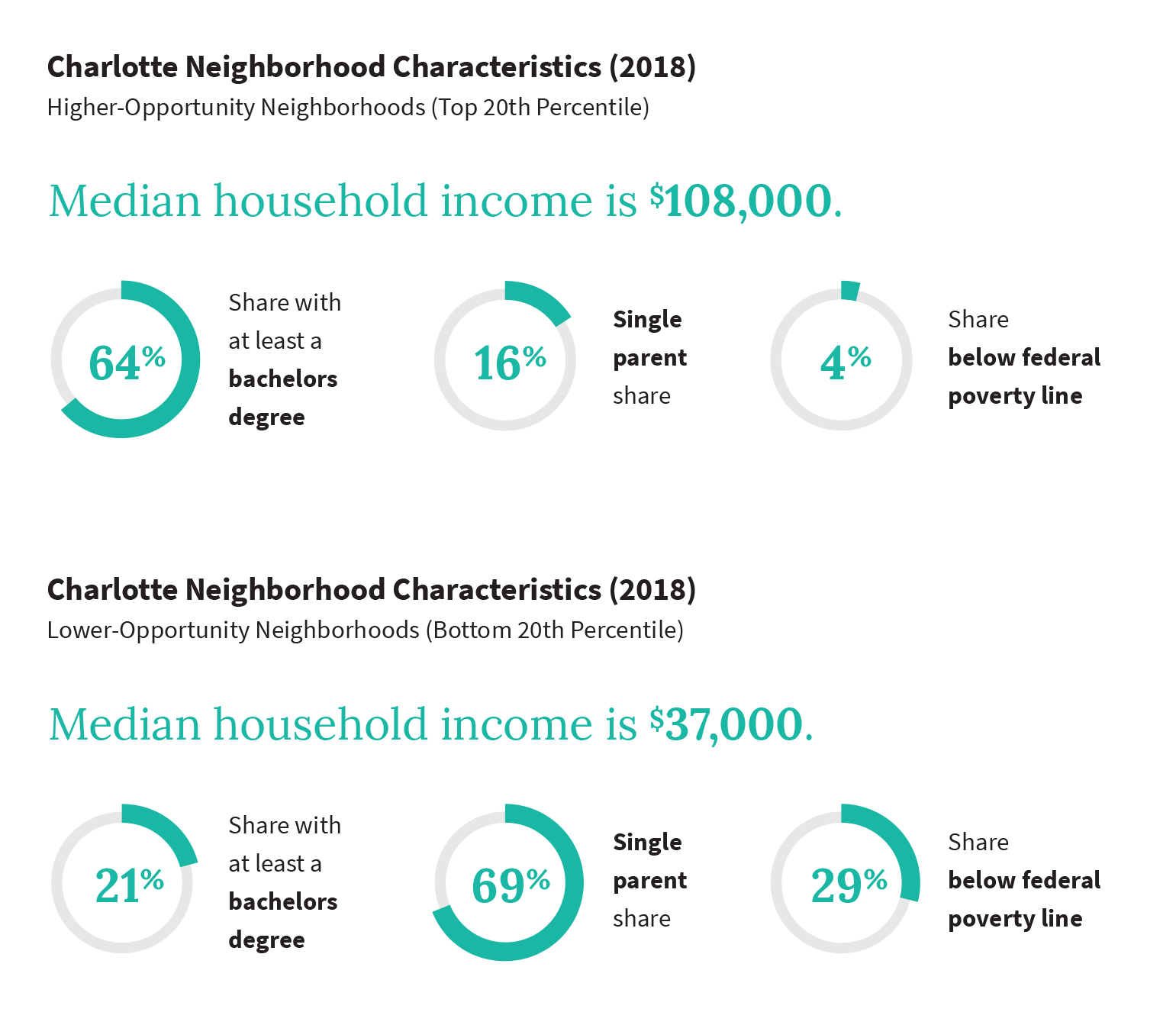

In Charlotte, neighborhoods with higher mobility rates for low-income children share several common characteristics. They are communities with higher median incomes and lower poverty rates, places where low-income children are more likely to be exposed to more middle- and higher-income families. Neighborhoods with more employed adults and a higher proportion of college graduates also have higher rates of upward mobility. Higher performing schools, higher levels of social capital, and greater family stability in a neighborhood are also associated with higher outcomes for the low-income children that grow up in that community.

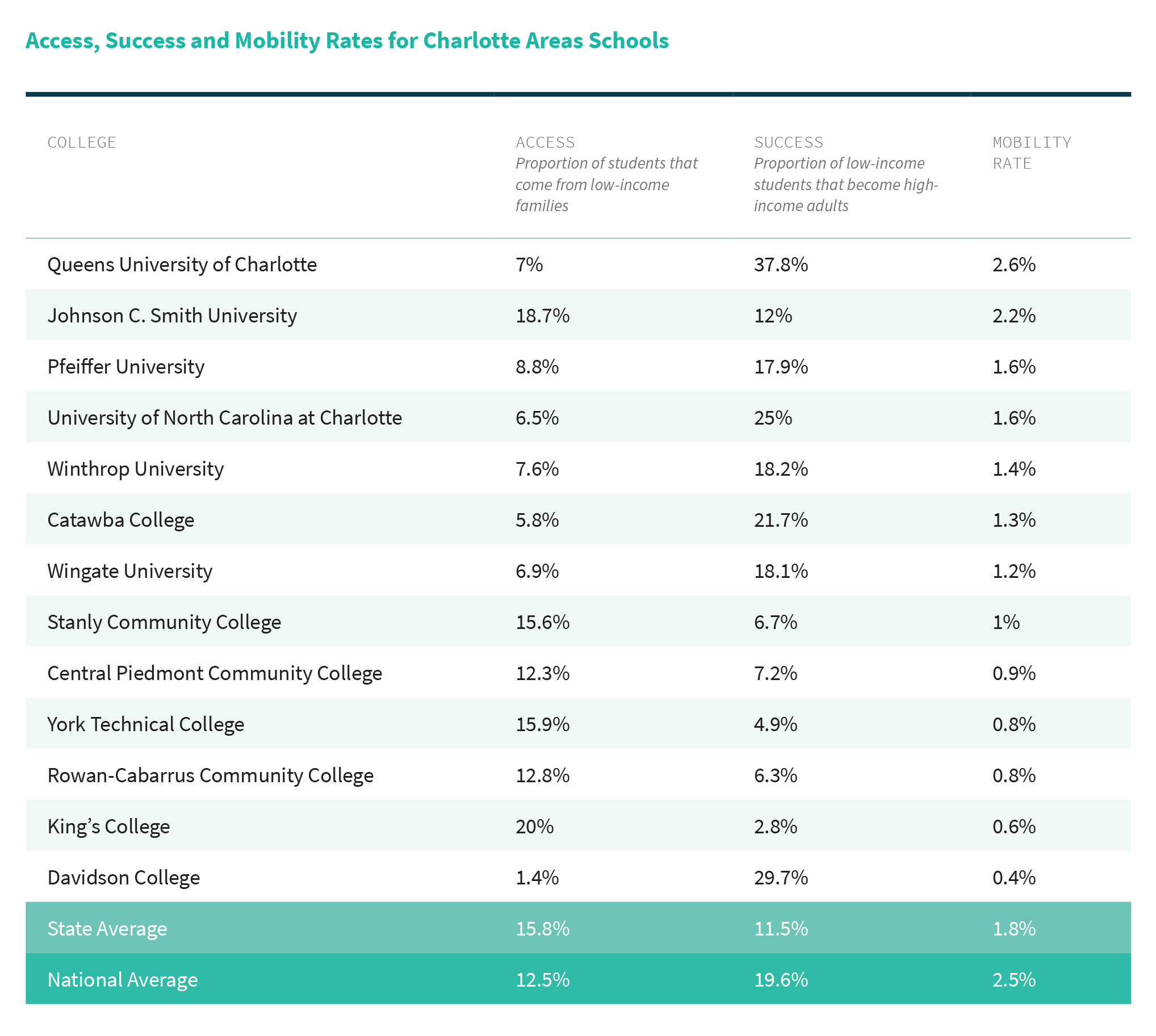

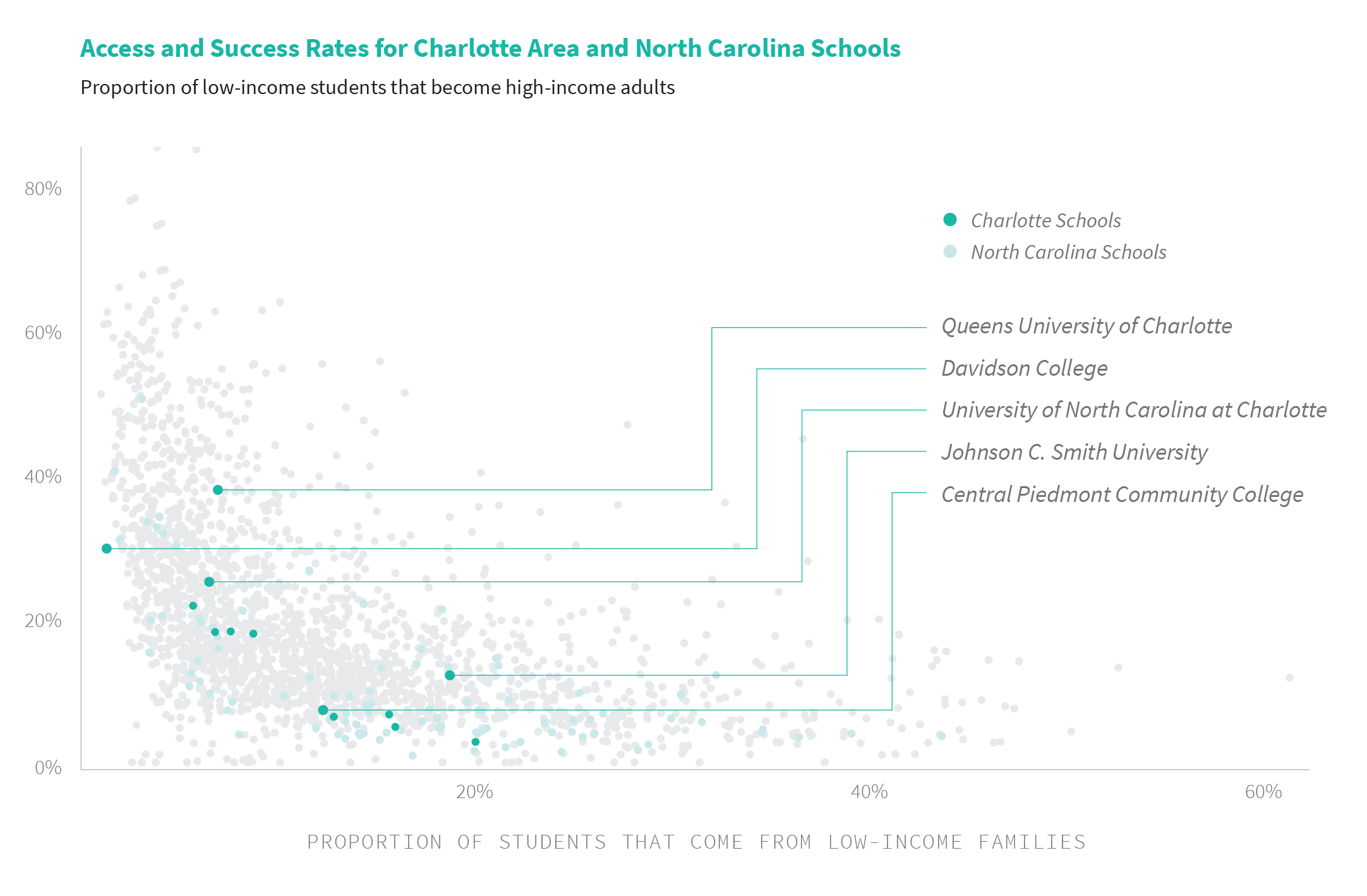

Many colleges and universities are successfully able to help their students, regardless of if they come from low-income backgrounds, rise up the income ladder. However, many of these schools have relatively few students from low-income families. A school that serves as a true engine of economic mobility for a community is a place that enrolls a significant number of low-income students and those students have a high likelihood of entering the job market and becoming economically successful.

We can calculate an economic mobility rate for every college by multiplying those two factors: access and success rates — the share of a school’s student body who come from low-income families and the chance that those low-income students will become high-income adults. Schools in the Charlotte region have a wide range of economic mobility rates.

Queens University and Johnson C. Smith University have relatively high mobility rates and Johnson C. Smith is especially successful at moving low-income students into the middle class.

Students at the University of North Carolina Charlotte and Davidson College have high success rates but could improve their mobility rates by increasing access.

Central Piedmont Community College serves a larger number of low-income students from Charlotte and could increase mobility by increasing success rates.

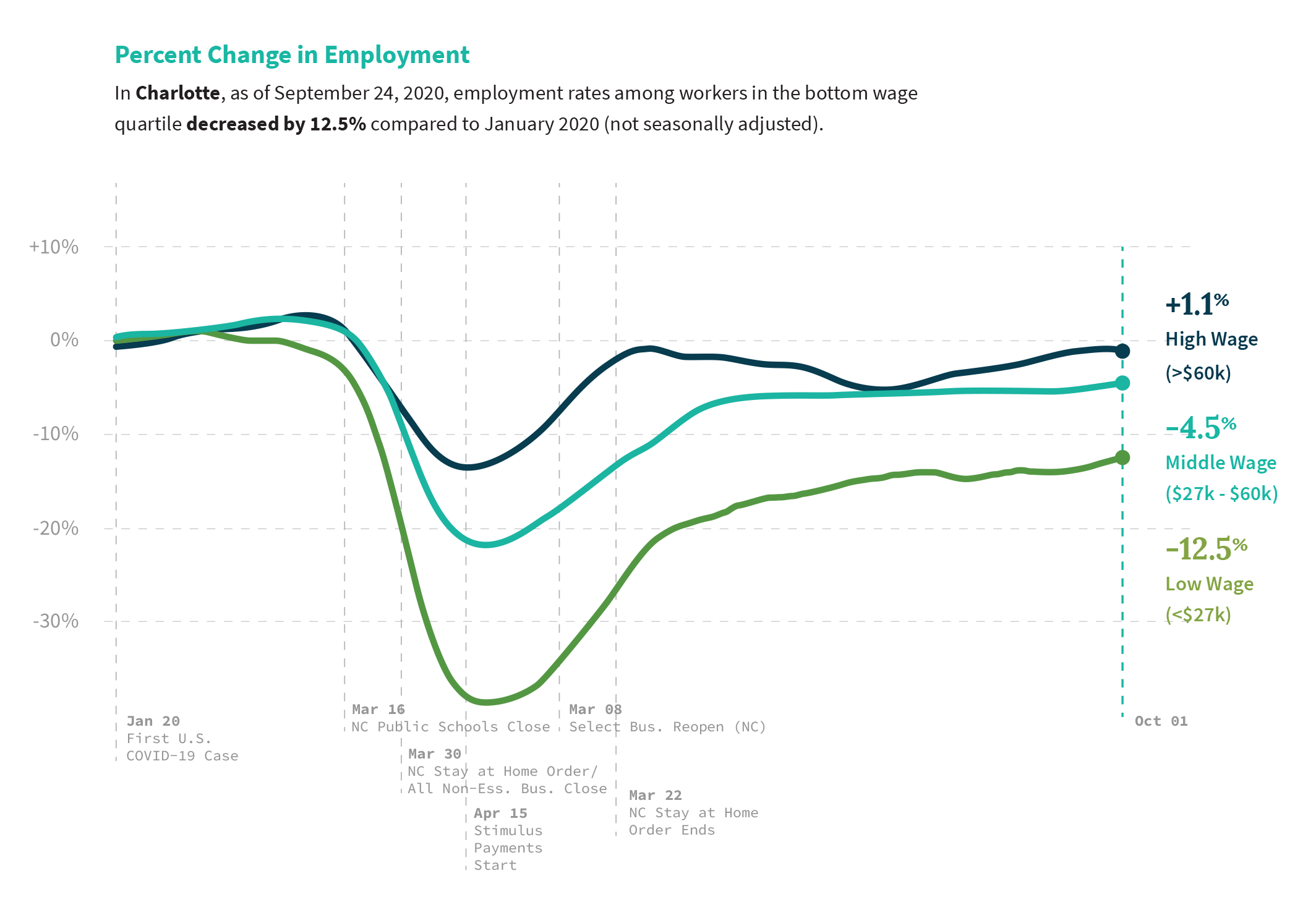

Charlotte and North Carolina’s economy has been hard hit by the pandemic. As of June 2020, over 500,000 unemployment claims were filed across the state. By mid-April, consumer spending had decreased by over 50%. Low-income workers were especially hard hit throughout Charlotte and Mecklenburg County, but especially those working in more affluent areas where consumer spending has dropped the most. For example, during the spring, employment rates dropped by 45 percent for low-income workers working in the wedge near wealthy neighborhoods like Ballantyne.

As inequality has increased, our economy has become increasingly interlinked; low-income workers are becoming more and more reliant on the consumption and spending patterns of the wealthy. Municipal budgets and important programs and services will also likely face financial strain due to decreased tax revenue.

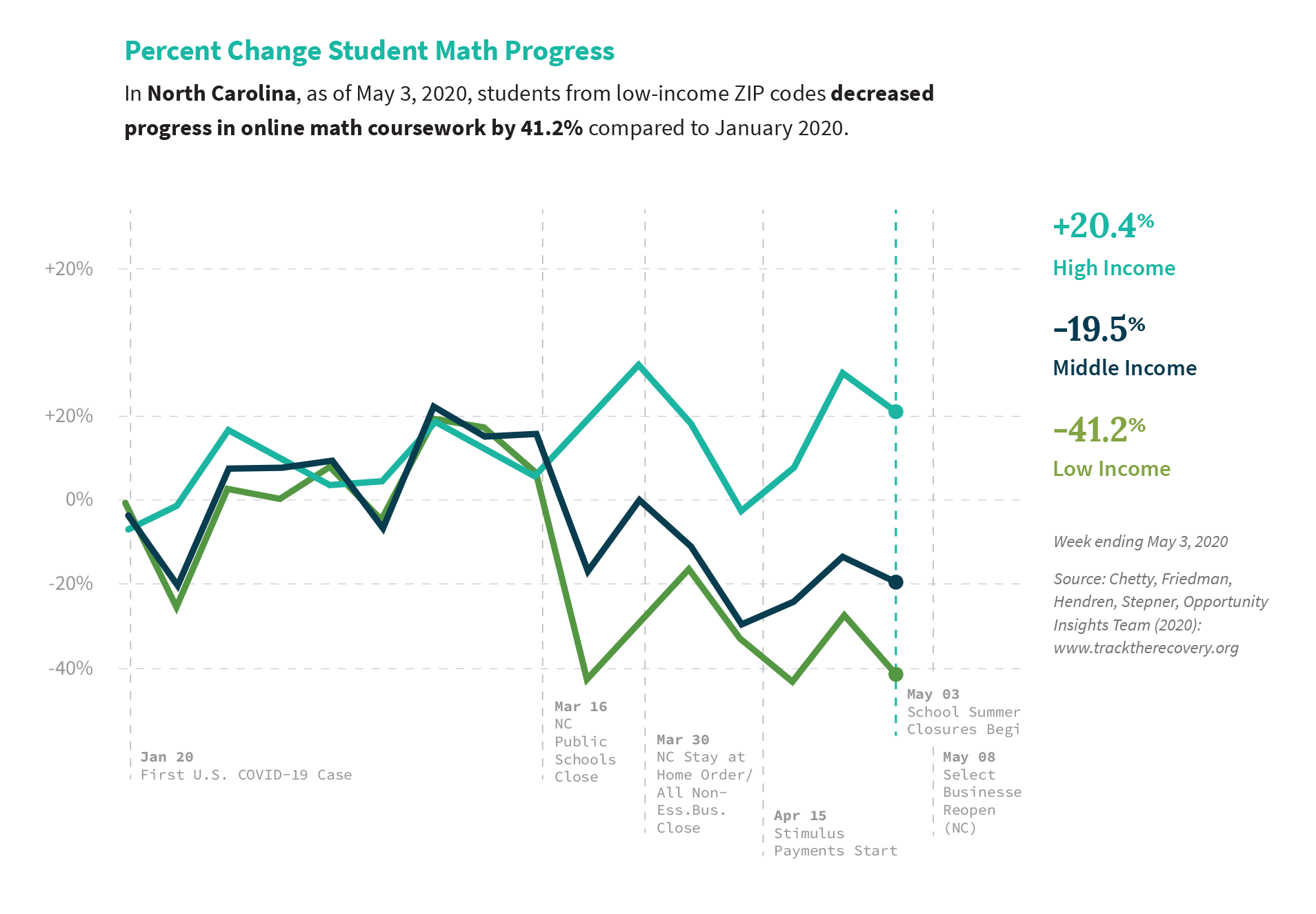

Achievement gaps for students may also be increasing. By tracking data from the learning platform Zearn, we can see that since schools shut down in March, Charlotte saw lower levels of student engagement and academic progress than almost every other large metropolitan area in the country. Specifically, student participation in schools using the platform dropped by almost 75 percent in Mecklenburg County in the six weeks after students transitioned to at-home learning. Low-income students have been especially hard hit. In North Carolina children in low-income and middle-income neighborhoods are much less likely to participate and make progress in online coursework than their counterparts in higher-income communities.

What does this mean for policy?

Given the landscape of economic mobility in Charlotte and the current research and evidence on effective policies, three Policy Action Areas have been identified. These Areas — investing directly in the health and education of low-incoming children, deconcentrating poverty and decreasing segregation, and increasing access to higher education — are strategies local leaders and stakeholders can begin to implement immediately and should be central to any comprehensive economic mobility strategy.

Invest in Low-Income Children

The outcome gaps we see between children raised in low and high-income households begin early and persist through adulthood. Direct investments in the health and education of low-income children are some of the most effective means of improving economic mobility rates and decreasing inequity. Increasing access to high-quality preschool, ensuring students have skilled teachers and sufficient educational supports, and providing adequate healthcare are proven strategies for increasing opportunity. Charlotte and Mecklenburg County have already made significant progress expanding early care and Pre-K access. Continuing to expand these and other evidence-based programs and initiatives that directly support low-income children must remain a priority and have the potential to create tangible impact.

Decrease Segregation: Housing Mobility

While additional work is needed to better understand how to create opportunity in all neighborhoods, deconcentrating poverty and ensuring low-income families have access to a wider range of neighborhoods must be central to Charlotte’s immediate efforts to increase economic mobility. New investments and commitments to affordable housing in Charlotte provide an important opportunity to increase housing stability for the region’s most vulnerable residents. However, given the current demographic patterns in the city and county, well-intentioned housing policies and investments have the potential to perpetuate the patterns of segregation that drive low outcomes throughout the community. Fortunately, promising programs and policy strategies exist that could significantly reduce segregation in Charlotte and increase upward mobility for thousands of low-income children.

Higher Education

Along with ensuring children receive access to healthy neighborhoods and needed support programs, increasing access to higher education can also serve as a method to increase opportunity. Many selective colleges and universities level the playing field across income groups and help propel students from low-income families into the middle class and beyond. Unfortunately, most low-income students in Charlotte do not have access to these types of institutions. Increasing college access generally and specifically increasing the number of low-income students that attend selective colleges like the University of North Carolina at Charlotte (UNC Charlotte), are additional means of increasing economic mobility.