Neighborhoods

Neighborhoods Matter

Children's lives are shaped by the neighborhood they grow up in

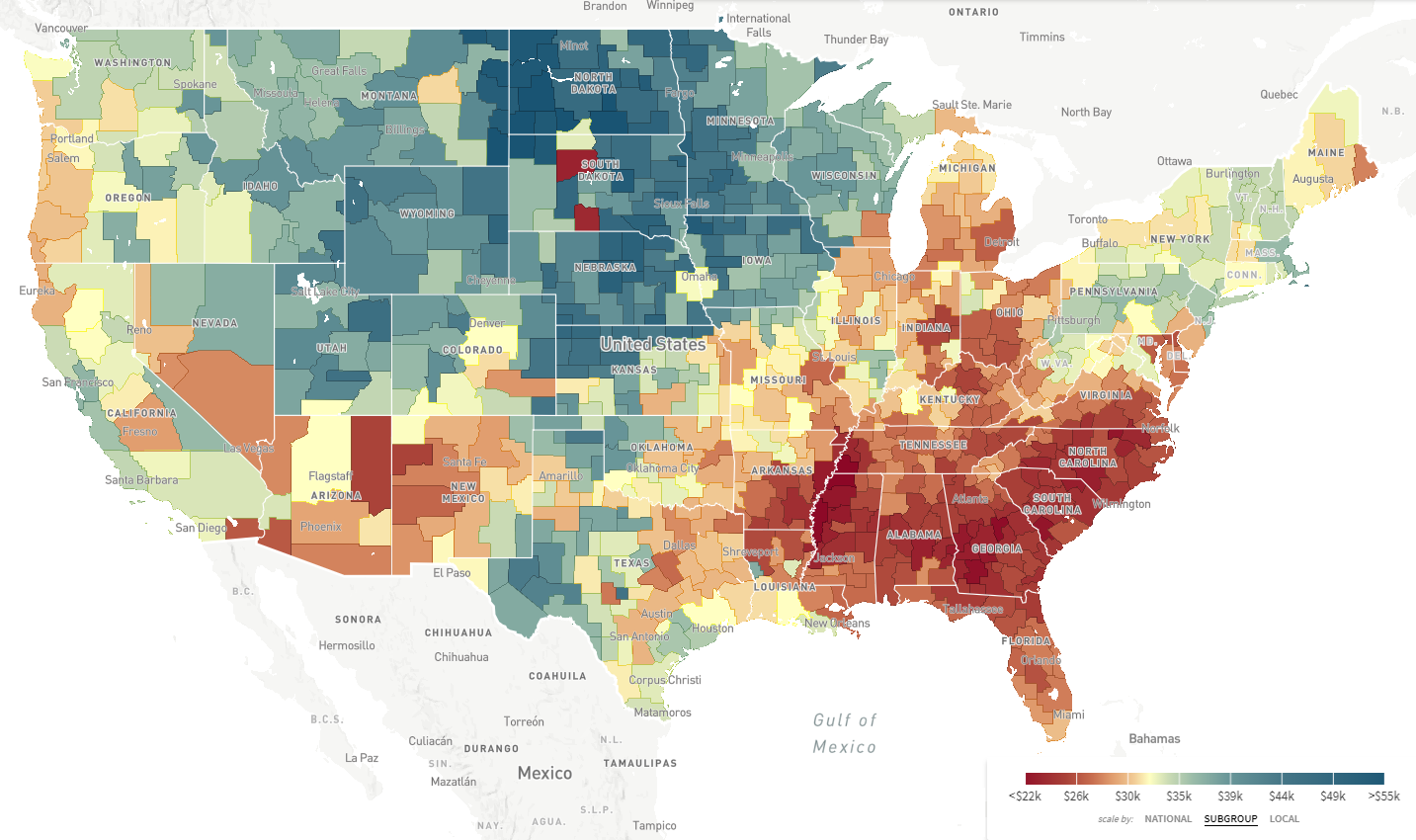

In a series of studies beginning in 2014, we have shown how the neighborhoods in which children grow up shape children’s outcomes in adulthood. Most recently, in collaboration with researchers at the U.S. Census Bureau, we constructed the Opportunity Atlas. This new interactive mapping tool presents estimates of children’s chances of climbing the income ladder for every 70,000 neighborhoods across America.

Social mobility varies widely both across cities and across neighborhoods within cities in the U.S. On average, a child from a low-income family raised in San Jose or Salt Lake City has a much greater chance of reaching the top than a low-income child raised in Baltimore or Charlotte. However, the Opportunity Atlas shows that there are neighborhoods within Baltimore and Charlotte that have higher rates of upward mobility than the average neighborhood in San Jose or Salt Lake City.

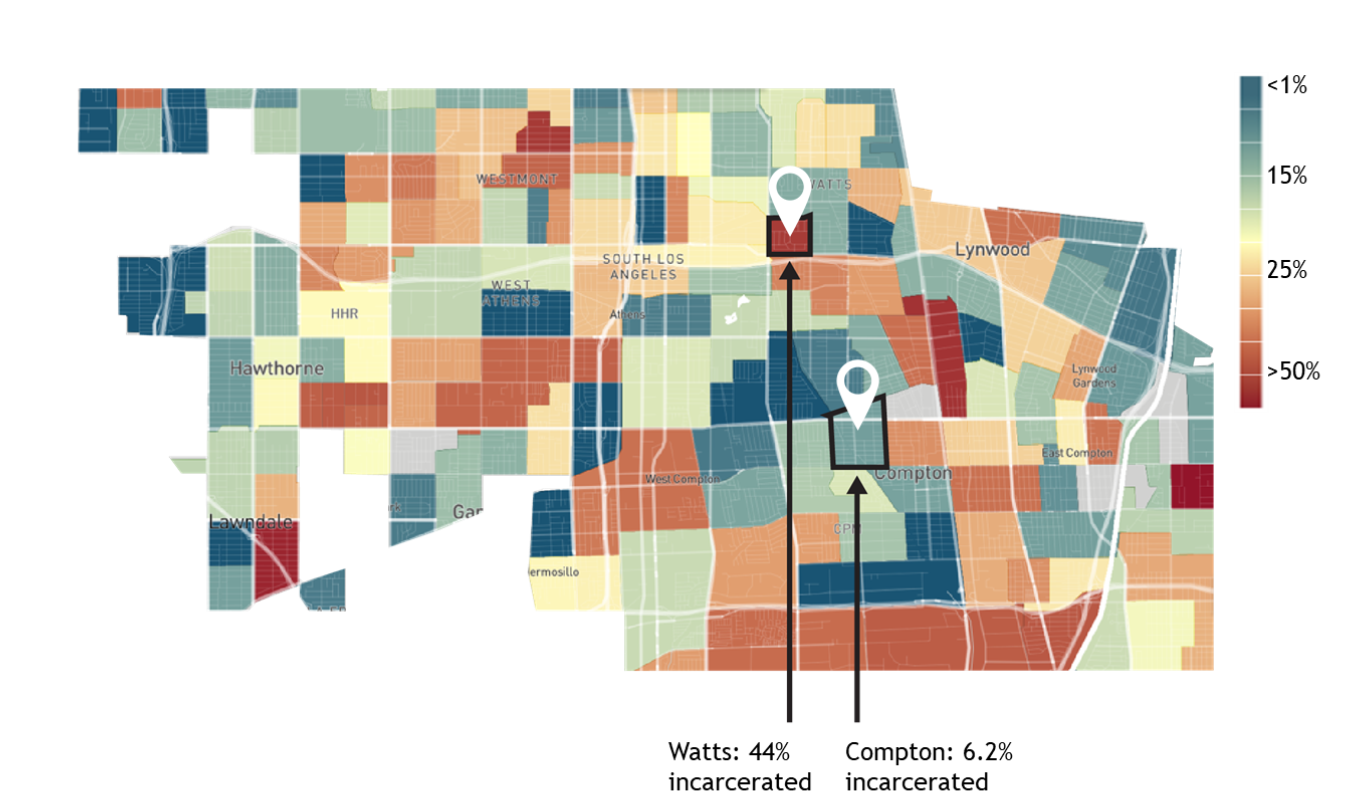

Of course, social mobility is about more than just earnings. Recognizing this, the Opportunity Atlas also provides information on other key indicators such as incarceration rates, college attendance rates, fertility rates, and marriage patterns. As with income, we find very sharp differences in children’s outcomes on these other measures as well.

Incarceration Rates for Black Men Raised in the Lowest-Income Families in Los Angeles, by Neighborhood in which they Grew Up

Click here for an interactive version of this map to see data for your own neighborhood.

Through a series of experimental and quasi-experimental studies, we find that neighborhoods affect children’s long-term outcomes through childhood exposure effects: every extra year a child spends growing up in an area with better outcomes on the Opportunity Atlas causes the child to have better outcomes in adulthood. This finding is encouraging because it shows that rates of upward mobility can be changed: indeed, within any given city, there are often neighborhoods that have rates of social mobility comparable to those in countries with the highest rates of mobility in the world.

Click here for Our Papers on Neighborhoods

Key Findings

- Moving within one’s metro area from a below-average to an above-average neighborhood in terms of upward mobility would increase the lifetime earnings of a child growing up in a low-income family by $200,000. Children who grow up in better areas are also less likely to be incarcerated and are less likely to have teen births.

- By studying outcomes for children who moved between neighborhoods during childhood, we show that every year a child spends in a higher-mobility environment increases their earnings in adulthood.

- Most of the 2.2 families who receive Housing Choice Vouchers currently live in relatively high-poverty, low-opportunity neighborhoods. We find that this pattern is a result of barriers that prevent these families from moving to higher-opportunity neighborhoods.

- Our measures of children’s long-term outcomes are only weakly correlated with traditional proxies for local economic success such as rates of job growth, showing that the conditions that create greater upward mobility are not necessarily the same as those that lead to productive labor markets.

- Outcomes are not constant across subgroups. For children whose parents are in the bottom half of the income distribution, the correlation in earnings between whites, blacks, and Hispanics is only 0.6. Neighborhoods are not unidimensional: experiences within those neighborhoods vary by racial and ethnic group, and by gender.

- Conditional on characteristics such as poverty rates in a child’s own Census tract, characteristics in tracts that are two miles away are uncorrelated with a child’s outcomes.

What does this mean for policy?

Our results show that the question is not whether we can have high levels of upward mobility in America today; rather, we simply need to understand how to replicate the high rates of mobility we see in some of our neighborhoods to all communities.

These findings motivate local, place-focused approaches to improving economic mobility, such as making investments to improve outcomes in areas that currently have low levels of mobility or helping families move to higher opportunity areas. Our work directly identifies areas that are potential “opportunity bargains” and our policy team is currently working with local housing authorities in the Creating Moves to Opportunity Project to help low-income families move to such areas.

Of course, helping families move can never be a scalable solution to improve upward mobility in and of itself; ultimately, we must make investments to make all communities areas of opportunity. While our research does not yet directly identify which specific policies are most successful in improving neighborhoods, our broader findings and other related research provide support for policies that reduce segregation and concentrated poverty in cities (e.g., affordable housing subsidies or changes in zoning laws) as well as efforts to improve local public schools.

Much remains to be learned about the best ways to make such improvements. We hope the granular data constructed in our studies of neighborhoods will offer a platform to test and develop new solutions and look forward to partnering with local stakeholders and other researchers in these efforts.